San Juan Island residents can expect a large increase in oil tanker traffic in the coming months with the completion of the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion in British Columbia. The project was approved by the Canadian government back in June 2019, despite the reluctance of Washington state leaders, who were largely left out of the conversation. The project will triple the amount of Alberta crude oil that is carried from Burnaby near Vancouver, B.C., aiming to increase the number of tankers sent out, from an average of five per month to one per day. The Journal spoke with leaders in emergency response and environmental advocacy on San Juan Island to learn more about what this increase might mean for the islands.

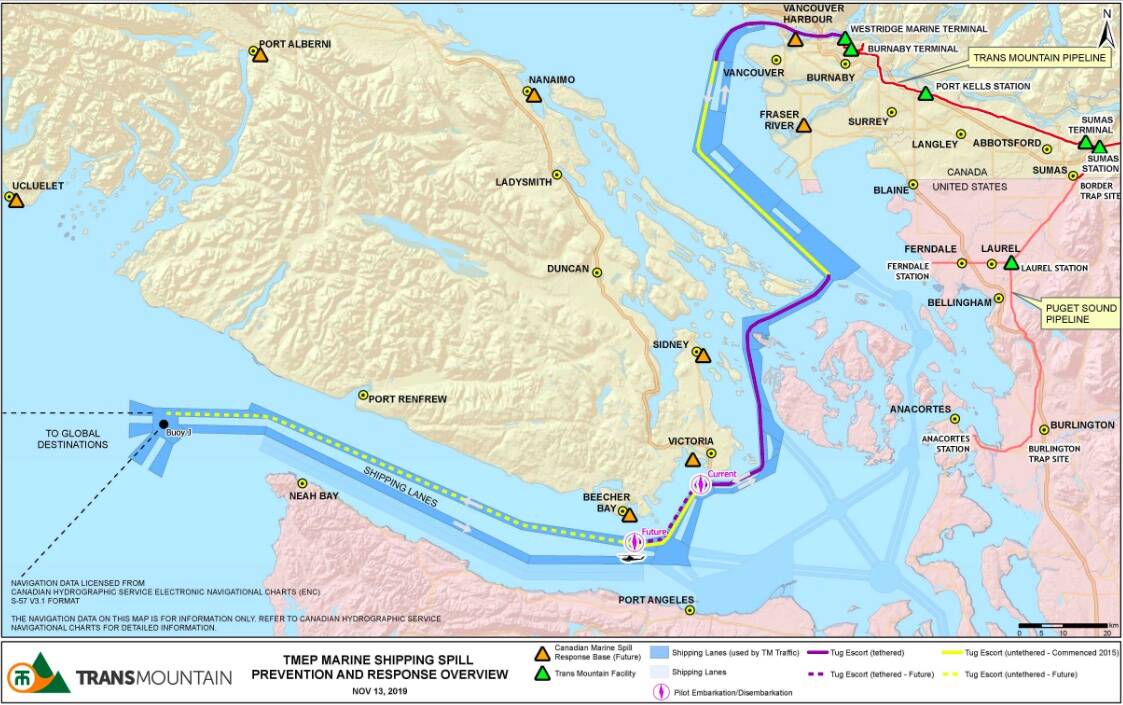

The expansion project is a twinning of the existing 1,150 kilometer pipeline which passes by the west side of San Juan Island and the Olympic Peninsula. According to their website, the pipeline has operated without a single spill since it began loading marine vessels with oil at its Westridge Terminal in 1956. As part of its approval of expansion in 2019, the pipeline is subject to 156 enforced by the Canada Energy Regulator. Additionally, according to an article from the Seattle Times, Trans Mountain has also invested in additional oil spill prevention and response measures at multiple new bases on Vancouver Island near the international shipping lanes, as well has agreed to employ tug escorts all the way to the western entrance of the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Lovel Pratt, Marine Protection and Policy Director at Friends of the San Juans, is still greatly concerned about the increase of oil tanker traffic near the San Juan Islands.

“This increase in tanker traffic increases the risk of accidents [and] also increases the risk of oil spills. A major oil spill would be environmentally, culturally and economically devastating,” said Pratt. Pratt cited an estimate based on 2006 numbers given by the Washington Department of Ecology (DOE) that a large oil spill could cost the state $10.8 billion and 165,000 jobs.

As for environmental impacts, one species that is particularly vulnerable to potential negative impacts of the pipeline are Southern Resident killer whales. Pratt mentioned that increased traffic could potentially lead to accidents such as ship strikes that kill whales, and that a major oil spill could even cause the extinction of the already critically endangered Southern Residents. Even without a major oil spill, Pratt stated that the increase in noise and presence of tanker traffic still impacts the Southern Residents and other marine creatures.

Pratt cited the application for the pipeline expansion project, saying it identified Turn Point, off Stuart Island, as having the “greatest level of navigation complexity” for the entire passage through the Salish Sea, and that Turn Point “also has high environmental values,” adding that a tar sands spill could also include severe air quality impacts.

“I have not seen any assurances that Canada is prepared to contain and collect a tar sands oil spill that has submerged and/or sunk to the floor of the Salish Sea, and that will likely happen, especially if the spill occurs in Haro Strait and Boundary Pass,” said Pratt.

According to Brendan Cowen, Director of Emergency Management for San Juan County, there are many factors that impact how successful a response can be to a spill, such as weather, available daylight, and tidal conditions, but he reiterated that the impacts of a large spill will always be significant and have significant effects on the environment. Cowan emphasized the importance of preventing spills before they happen with different regulations and protocol.

“While vessel traffic is an indicator of spill risk, it is important to note that with strong regulation, implementation of best safety practices, and instilling a culture of risk management, higher volume doesn’t always mean higher risk,” said Cowen. “We can look at air travel as an example: flying has never been safer than it is today, despite enormous increases in passenger miles flown.”

Cowen believes that Washington is doing a good job with different measures such as requiring things like escort tugs for oil laden vessels, and double-hull tankers, and a strong vessel traffic control system. In fact, he said that at times he is more concerned about a spill from a cruise ship, ferry, or cargo tanker as opposed to an oil tanker.

Still, Cowen recognizes that the risk of a devastating spill is still present, and acknowledges the problematic nature of US representatives being left out of the conservation.

“There will always be a risk of a major spill, and the complexities of a Canadian project resulting in impacts to US communities but without the benefit of US regulation or requirements is certainly an added wrinkle,” said Cowen.