By Kathryn Wheeler

Sounder contributor

To many, San Juan County feels far away from the rest of the world, and consequently, from the world’s problems. The islands seem to move slower, and worldly chaos, such as the natural disasters of fire and floods seen just across the Salish Sea, doesn’t often find its way here. This separation can give the impression that the islands are immune from these issues.

That was until 10:20 a.m. on Oct. 20, when the yearly ShakeOut Earthquake drill occured, for which 2,027 county residents, half of them school children, participated this year. The annual event reminds many islanders that underground, a world of immense activity and destruction lies.

The annual ShakeOut drill — a collaboration between Federal Emergency Management Association and six U.S. geological organizations and research centers — began in Southern California in 2008 as a way to educate residents on how to prepare for earthquakes in the most earthquake-prone state in the county. The drill is simple: “drop, cover and hold on,” three steps considered life-saving in the event of an earthquake.

“It’s not complicated but the hard part is just doing it,” said Brendan Cowan, the County’s Emergency Management Director since 2003.

The drill attempts to build a muscle memory response in the event of an earthquake, which will allow a person to act, instead of thinking first, saving precious seconds in case of an event. Although it is rare for islanders to feel the shaking of an earthquake, small, unfelt earthquakes happen constantly in the San Juans.

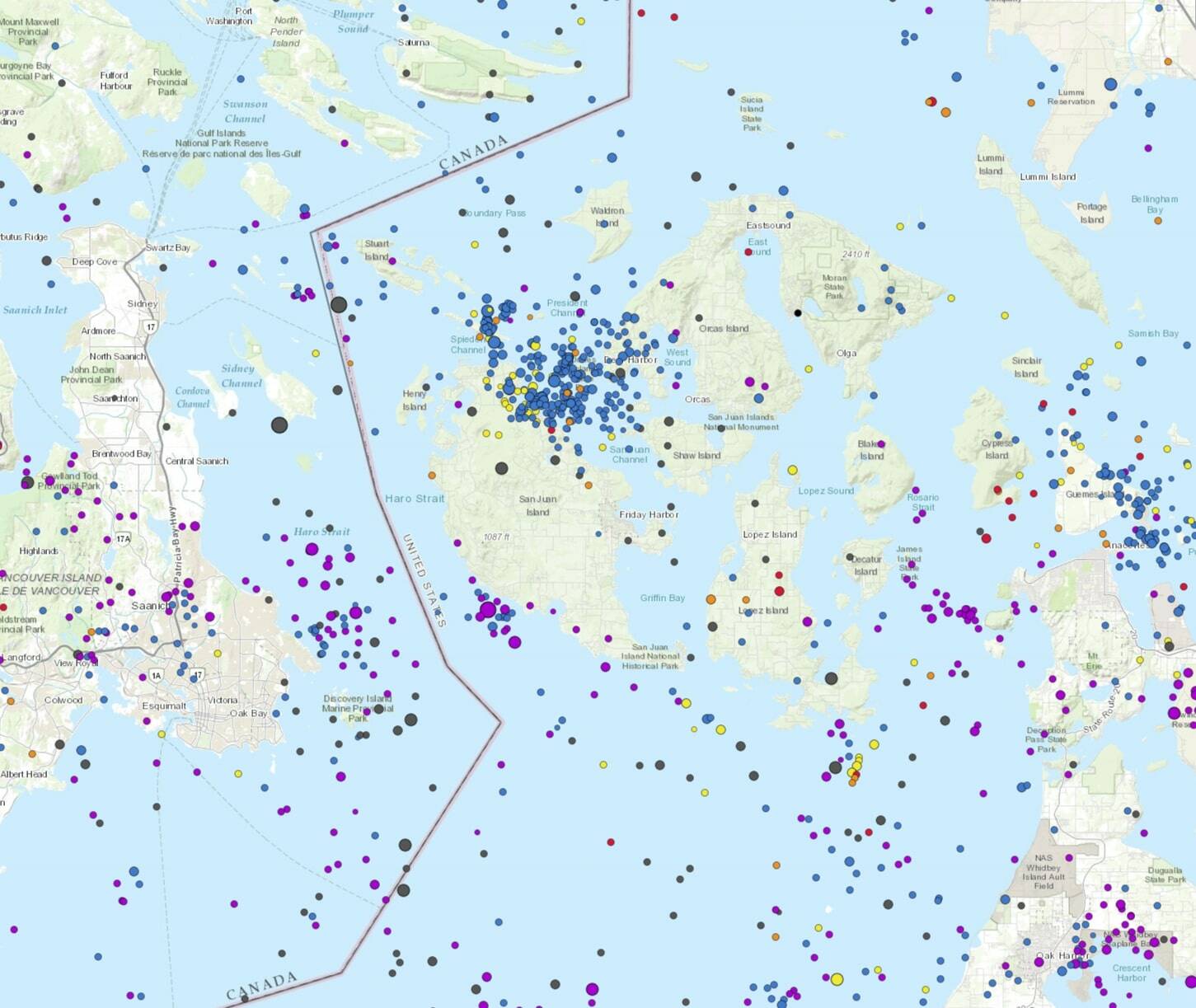

The accompanying map shows the prevalence of earthquakes since 2o00.

“Almost all of [those earthquakes] are too small to feel, but we detect them and locate their epicenters. Data like this tells us about the locations of faults and the buildup of stresses in the Earth’s crust,” said Harold Tobin, Seismology and Geohazards expert and professor in the Department of Earth and Space Sciences at the University of Washington.

Washington state faces the second highest risk of damage from earthquakes in the country, second to California. This is largely due to its position atop the Cascadia subduction zone, an area where one tectonic plate, an ever-shifting slab of rock beneath the earth’s surface, is gradually sliding eastward underneath the continental North American plate, a process known as subduction. Eventually, the sliding slab will reach a stopping point at the unmovable mass of the earth in the center of the continent. When this happens the Cascadia subduction zone will give way, causing a major earthquake, projected to be between magnitude 8-10 (the scale stops at 10).

This kind of gargantuan earthquake naturally seems like a terrifying prospect, and it was for the many indigenous tribes who experienced this exact quake around 1700, according to oral records of the event. Many of these populations along Puget Sound were wiped out as land fell into the sea and a major tsunami crashed onto the coastline.

However, this fate is something scientists are working hard to avoid and times have changed dramatically. Preparedness efforts, such as the ShakeOut drill and emergency alert systems provide, intend to protect many from such devastating consequences.

According to Tobin, an earthquake of this size—termed “the big one” by scientists—is estimated to happen roughly every 200-550 years based on historical records. This means “the big one” could happen tomorrow or in another 200 years. Of more concern to Tobin, however, are the smaller, more frequent earthquakes. These smaller events tend to be farther from people’s minds as they feel less threatening, yet have more frequent and reliably destructive outcomes.

The Devils Mountain fault, which sits just south of the islands, causes one of these more frequent earthquakes, producing a significant earthquake every couple of decades. Veteran islanders may remember the 2001 Nisqually earthquake, which had a 6.8 magnitude that rocked the Puget Sound area and was felt as far as Idaho. While no direct casualties occurred, many were injured and property damage was estimated between $1-4 billion.

While the threat of earthquakes is very real, both Cowan and Tobin believe there is a lot of good news for the islands, which have unique characteristics that may be game-changers in major earthquake events. This starts with the geology of the islands, which have high, solid rocky shorelines that are more resistant to crumbling and not as susceptible to being washed away by high seas.

The culture of resilience on the islands could be a lifesaver as well, according to Cowan. Islanders are used to power outages and are more thoughtful about how to supply their food in a place that has few lifelines to the mainland. In a major disaster, this can amount to better preparedness so long as residents remain aware of the fact that the islands are isolated, and preparedness is essential. Cowan also believes it is critical to “make sure we don’t let go of that culture of neighbors taking care of each other and helping people be prepared.”

A number of other changes could be implemented to better prepare the islands for natural disasters, including retrofitting buildings to be more stable and securing any heavy objects in homes and public buildings. Tobin oversees an extensive database of Washington buildings that are structurally sound enough to handle an earthquake. The data shows that the Pacific Northwest region is woefully underprepared for an earthquake, with most buildings ill-equipped to evade collapse.

However, according to Tobin, the islands are much better off than the rest of the state. Most buildings are made of wood, not glass or older stone, and stop at two stories, making them sturdier and more able to stay on frame and upright in the case of shaking.

The islands also have a uniquely small community full of citizens whose voices tend to hold more power than in a place like Seattle, with larger, less localized governing. If preparedness becomes a priority for residents, it may be easier to implement better safety measures more swiftly—retrofitting any unsafe buildings, helping residents prepare their homes, and getting more people to participate in yearly ShakeOut drills.

Beyond this, according to Cowan, it simply comes down to awareness and knowing what to do when an earthquake comes. It’s important to remember “Earthquakes are a fact of life…there’s a lot of things we can do to come through them safely,” echoed Tobin.

For Cowan, this means reducing one’s panic and anxiety by simple preparedness methods. In a world of heightened anxiety, he says he is “Spending more time reassuring people than spending time convincing them to do something.” He sees the ShakeOut drill as a way to reduce this commonly felt fear.

“The message that I like to give to people is that disaster preparedness does not need to be complicated, time-consuming, or expenseful, it really can be very simple. The one really challenging thing is making time to do it,” says Tobin. For this reason, the seemingly simple ShakeOut drill of “drop, cover, hold on” may in fact prove monumental when disaster strikes.

For more information on ShakeOut, go to https://www.shakeout.org/howtoparticipate/. To receive emergency alerts of an oncoming earthquake, download MyShake, which can be found in the iPhone App store, and is already built into Android phones.