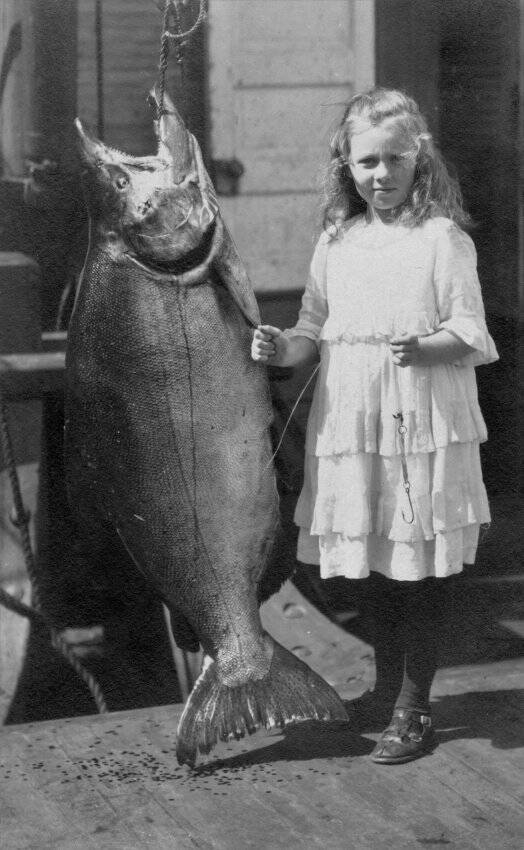

The original fishers of Chinook salmon, Southern Resident Orcas, coevolved with their prey hundreds of thousands of years ago. It only took a handful of the massive fish that once weighed up to 100 pounds each, to feed one whale per day. With the dwindling size and population of Chinook, the orcas are struggling for survival. To prevent the loss of both species, Wild Fish Conservancy, a Washington-based nonprofit, has filed a lawsuit in hopes to prevent overfishing by the Southeast Alaskan fishing industry. NOAA’s most recent review of the fishery, the analysis challenged in this lawsuit, concluded that under the existing management and recovery regimes over the last decade, salmon availability has not been sufficient to support SRKW or Chinook population growth. Even though this fishery contributes to that problem, NOAA approved continued harvest by citing speculative and unproven plans to mitigate the harm.

“I am deeply sympathetic to the economic harm to Alaskan communities and fishers as a result of NOAA’s failure to sustainably manage this fishery,” clarified Emma Helverson, Executive Director of Wild Fish Conservancy. “However the science is clear that this fishery cannon continue at these levels if we are going to be successful recovering the SRKW population and wild Chinook coastwide.”

The court ruled that the National Oceanic Atmosphere Administration needed to go back and correct serious violations of the Endangered Species Act and environmental law in the Chinook management plan for the Southeast Alaska troll fishery, and in the interim temporarily stopped the summer and winter salmon fishing season. Those two seasons are when, according to Helverson, approximately 97 percent of the fish caught originate in BC, Washington, and Oregon rivers, many of which are the fish SRKW prey upon.

“While communities throughout the coast have closed fisheries and made significant economic sacrifices to protect threatened and endangered Chinook populations in their home rivers, these same depleted populations are being harvested far from home in Southeast Alaska where they are marketed and sold as sustainable Alaskan Chinook,” says Helverson. “While this case is about conservation, it’s also about equity and we will continue to advocate for the conservation burden of protecting and restoring these species to be more equally shared by all communities who depend on them.”

The State of Alaska and the Alaska Trollers Association appealed the case, and request that commercial South East Alaskan trollers continue to be allowed to fish while the appeal is considered. The court granted that request.

“The …parties have established a sufficient likelihood of demonstrating on appeal that the certain substantial impacts of the district courts .. on the Alaskan salmon fishing industry out weight the speculative environmental threats posed,” the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ordered in June.

“The economic, ecological and cultural cost of losing the Southern Residents orcas and wild Chinook is unthinkable. It is unfortunate that the Ninth Circuit determined the short-term economic interest of Southern Alaska commercial harvesters should be prioritized over the long-term interests of the current and future generations of First Nations, Tribal Nations and communities throughout the Pacific Northwest who depend on the species” Helverson responded in a press release.

“It’s crazy because now they are being allowed to do this known illegal and unsustainable activity, [overharvesting]” said Dr. Deborah Giles, Science and Research Director of the nonprofit Wild Orca located on San Juan Island.

It is no small industry. According to the Alaska Sun, “[This] is a $30 million industry open nearly year-round, sustains the region’s island communities with jobs and tax revenue and claims more active fishermen than any other commercial salmon harvest in the state, except the one in Bristol Bay.”

An Associated Press article quoted Alaskan Senator Dan Sullivan saying “It’s great that the court recognized the irreparable harm this frivolous lawsuit would have on hardworking fishermen who have done nothing wrong,” he said. “It is patently ridiculous to believe a small boat, hook and line troll salmon fishery hundreds of miles away from Puget Sound is having more of an impact on the sustainability of Puget Sound orca whales than toxins, pollution, noise and vessel traffic in their own backyard.”

Helverson responded to the Journal that it does not matter whether one is catching the endangered species one by one or 200 at a time, the total accumulated catch remains the same. Helverson and Dr.Giles, also take issue with the argument that SRKW are struggling as a result of toxins and vessel noise as the primary culprits.

Dr. Giles has been researching the behavior and health of the SRKWs for years. Her research group uses unique noninvasive methods including using a dog to sniff out scat from the whales while it is floating on the surface. The scat is then carefully collected and analyzed. While they don’t have data back from last year yet, a study published in the “Ecsophere, an ESA Open Access Journal” analyzed aerial footage of the whales from 2008 to 2019 to determine if changes in overall body condition were connected to a lack of Chinook. The conclusion was that the health of J pod whales, who spends the most time in the Salish Sea, was influenced most by an abundance of Frazer River Chinook. Their body condition, the study found, was likely to improve or stay the same when the estimated salmon return was above 750,000.

The health of L pod whales health was more closely linked to Puget Sound Chinook; “The researchers found that when these fish numbered above 399,000, the whales’ body condition improved or was stable, but when the abundance shrank by 50%, they could not maintain their condition,” the press release stated.

The health of K pod whales did not align with a specific Chinook population, suggesting they “may forage on a diverse assemblage of prey,” according to the study, yet, similar to L pod, they appeared to benefit from a higher abundance of Puget Sound Chinook.

This does not mean other issues are not impacting them or that they should not be addressed.

“If you pull it apart, toxins, boats, pregnancy viability, are all major issues but lack of large and abundant prey is at the center,” Helverson said. Dr. Giles agreed, explaining that each whale needs 300- 400 pounds of fish a day, depending on the individual animal, pregnant whales and large males may need more. When Chinook ranged from 60-100 plus pounds, they only needed to catch a few per day to meet their caloric intake. Now, however, the average size of Chinook in Washington is only 12 ½ pounds, and there are far fewer of them. This means SRKWs need to work harder to catch less abundant, smaller fish.

“We actually see that they are foraging more and sleeping less,” Dr. Giles said, adding that there has been a concerning new behavior developing over the last few years. She and her fellow researchers call max spread. The animals once traveled either tightly together, or loosely or so somewhat spread apart, they are now traveling miles apart- just enough that they can still communicate but far enough that they all have a better chance of finding food.

Besides illustrating the degree to which the whales are struggling to find food, being spread miles apart impacts their social fabric. All three pods once joined to form a “superpod” sporadically through the summer months and self-isolated by pod during the winter when food is more scarce. This prevents prey competition between pods, Dr. Giles explained. Now the three are uniting less frequently and subgroups of each pod are splintering off more often. Since superpod meetings serve as occasions to mate with members outside the pod, those opportunities are also less frequent. A recent paper by NOAA noted that the Southern Residents were inbred, Giles said.

“They have always been a small population,” Giles said adding that the larger problem is that research is showing that 69% of pregnancies are not viable. The females either miscarry or the calf dies almost immediately after birth, as with J-35, Tahlequah, who became world-famous after being spotted carrying her deceased baby around for 17 days.

L pod welcomed two new calves this year, the first born to the pod in two years. Neither Giles nor Helverson was overly comforted by the news.

“While the recent new calves in L pod both seem to be healthy, the fact is that the SRKW population should be having six or more calves a year,” Giles said.

With summer temperatures predicted to be hotter than ever (warmer ocean temperatures have been thought to impact salmon survival rates) she fears it will be a dismal year for salmon returns, and what that may mean for the whales, humans and the entire habitat that relies on them.

Salmon are woven so deeply into the ecosystem, history and culture of the Pacific Northwest if one cored giant evergreen trees along the coast and rivers they will find the genes of these fish. Bears, badgers and other species also prey upon the species, carry their catch into the woods where they feast at the base of the trees, and eagles perch in the tops of trees eating their fish, dropping bits of scales and bone as they eat. Without salmon, the very plants of the Pacific Northwest would be permanently altered.

“What is at stake is the collapse of the entire ecosystems that the presence of salmon helped create,” Dr. Giles said.

Local fishermen have already noticed the change.

“What’s concerning is what isn’t being seen out on the water,” said Jay Julius, a member of the Lummi Nation. Lummis call themselves Lhaq’temis, people of the sea. His grandfather, who shares his traditional name Nw’etot Iheim, was a reef netter on Orcas Island. Julius is the new owner of Friday Harbor Seafood at the Port of Friday Harbor.

“It’s what we don’t see or can’t see that is the most concerning to me, that we are witnessing a species called, qwe ‘lhol mechen [Lummi for Orca] that is on the brink of extinction and starving and struggling. You see a lot on the water, but it isn’t abundance anymore, it’s struggle. ”

Qwe ‘lhol mechen translates to relations under the waves, reflecting the close kinship Lummis and many tribal nations feel toward the whales.

“This is not something brand new. It’s been happening over time. It started in Europe, and then on the East Coast, its culture, a culture driven by money. We know what the end result will be when driven by money,” Julius said, citing animals already extinct.

According to Helverson and Dr. Giles, Chinook and other fish species declines can be traced 150 years ago when fishing ceased to occur near or in the rivers of origin and commercial fishing took to the seas. Today, some industrial fishing boats do not even come to shore to offload their catch and get supplies. Large boats carrying ice go out to them and bring the catch back to shore. The result is an efficient fishing machine equipped to kill hundreds of thousands of Chinook before they are able to return to their native rivers to spawn. In the past, Chinook spent seven or more years in the cold nutrient-rich waters, and now most spend three to five years at sea before they return to their natal rivers to spawn.

“In less than two centuries we have unraveled thousands of years of evolution,” Dr. Giles added.

NOAA falls under the Department of Commerce, putting them in the awkward position of advocating for the endangered species, salmon, as well as the needs of its constituents, including the fishing industry. Salmon, particularly Chinook, are the only federally listed endangered species humans are allowed to kill, Dr. Giles pointed out.

Chinook salmon native to British Columbia, Oregon and Washington state that are caught in Alaska are branded “Alaskan caught” and sold around the world. Consumers think they are purchasing a sustainably harvested salmon but, in many cases, they are actually eating runs of Chinook that are on the endangered species list, Dr. Giles noted.

Rather than discussing catch limitations or other changes in fisheries practices, money has been thrown into salmon hatcheries. Millions of dollars, according to Helverson, are slated for various hatchery projects in the region. NOAA recognizes hatchery impacts as one of the four leading causes of decline of wild salmon, in addition to harvest, hydroelectric dams and habitat loss. In most cases, hatcheries have been shown to be not just ineffective in recovering wild fish, but detrimental to wild salmon stocks through weakening the wild fish genetics when they breed with them, and by competition for food, rearing habitat and other resources.

“We are scraping the bottom of the barrel, and it’s because of how and where we allow fishing to occur and it’s not working. It’s not working for the fish, for the whales or for the tribes,” Dr. Giles said, explaining that to manage fish properly, fish should be allowed to exit their native rivers, go to sea and come back again before harvesting them.

To ensure enough is left for SRKW, the whales should also be included in the harvest calculations.

Ultimately Helverson and Dr. Giles both recommended consumers know not just where their fish is being caught, but know who caught them as well. Returning to traditional methods in the rivers and along the coast would return control to local communities. Hatchery fish could easily be prevented from going to spawning grounds, and wild salmon would have the opportunity to fulfill their at-sea cycle of life.

Julius liked the concept of returning to the traditional ways of fishing but was not sure it was feasible. “Realistically, we are too deep in our ways now,” he said. While that sounds pessimistic, he is not without hope.

“Without hope we are lost. I hold hope in our youth but they have anxiety like we can’t imagine. The rivers are going dry the salmon the orcas struggle. Our youths’ anxiety is being played out while we are managing to extinction. Imagine being a child, a teenager right now. But I do hold hope in our future. We have to fight the fight and not give up.” Julius said. “How do we invite others to take heart, to understand, because that is where we will shift.”

NOAA continues to work on its management plan. This summer the State of Alaska, and the Alaskan Trollers Association are expected to file briefs in the lawsuit later this summer, and the Wild Fish Conservancy will file theirs in the fall.