Issa Wild has only built five tiny homes for islanders since he started his Orcas Island construction company two years ago.

“We’re trying to build more houses and make it affordable, but the county regulations are really restrictive,” said Wild, owner of the homebuilder Cascadia Homestead.

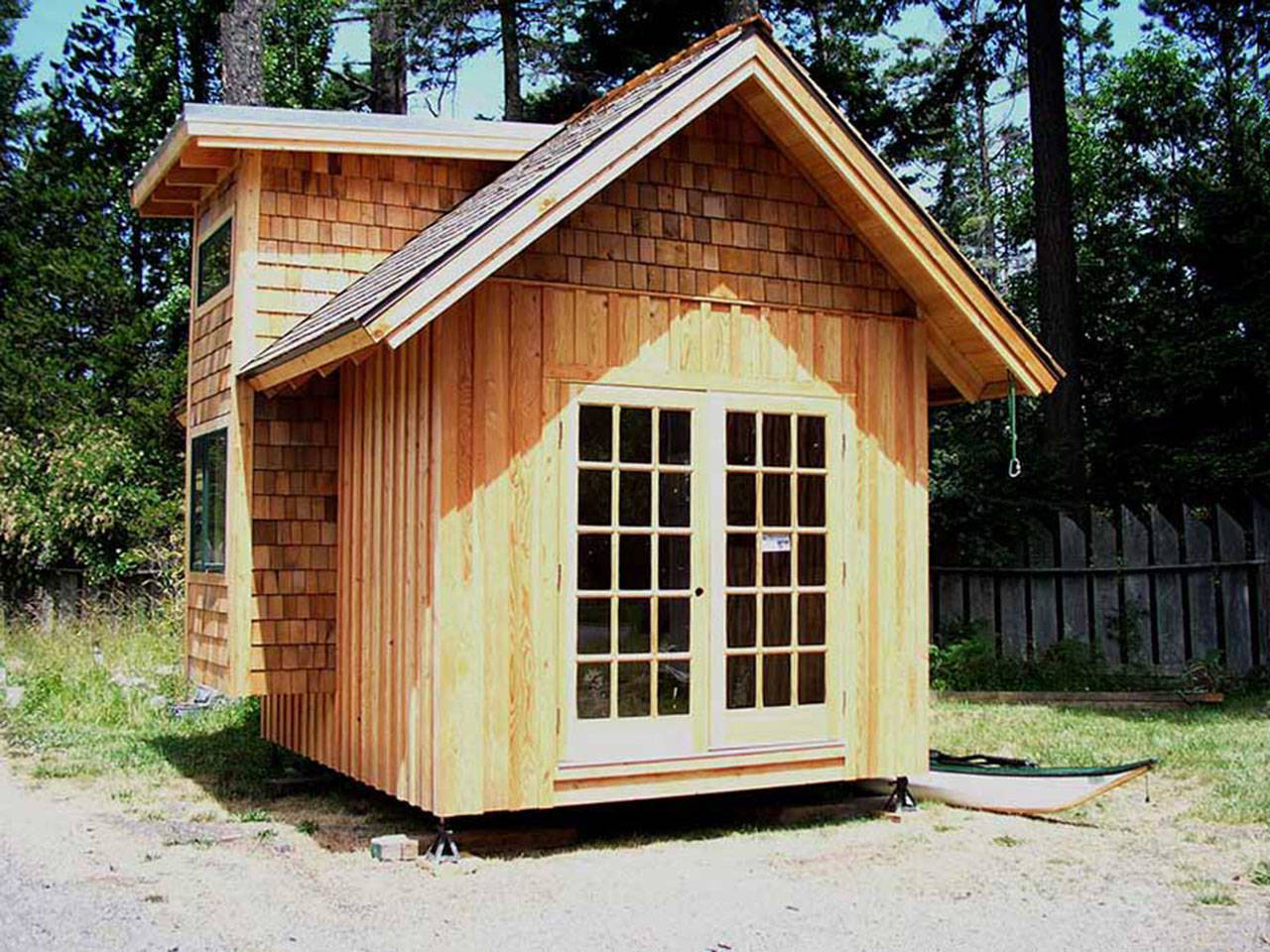

Mostly, Wild builds other structures, like sheds, because county code hasn’t caught up to this national movement towards minimal living, spurred after the 2008 recession when many Americans lost their homes.

Like in many parts of the U.S., there are no local rules that address tiny houses, specifically. This creates a “gray market,” said Wild, where many of his tiny house buyers aren’t permitting them as homes, but temporary, moveable structures in rural areas.

Tiny homes can range from the size of a shed, about 100 square feet, to the size of a garage, about 700 square feet. They can be placed on a trailer or foundation. Wild sells roughly 200-square-foot models from $22,500 to $54,800, depending on style and amenities.

That’s significantly lower than most county homes, where the median price hasn’t fallen below $300,000 in the last decade. U.S. Census data shows 36 percent of county homes are vacant, possibly being used as vacation homes. This could be the reason behind the county’s lack of long-term rentals.

A possible solution for affordable housing — mentioned by islanders from county councilmen to builders like Wild — is tiny homes.

On the islands, setting up a home in rural areas can be costly. Homeowners must buy land and usually install a septic system, which can cost up to $40,000, in addition to the several permits needed. This high cost encourages islanders to build bigger homes, said Wild; why spend $100,000 to make your home inhabitable and only live in a 700-square-foot structure?

The more cost-effective way to live, said Wild, is sharing land. However, in rural county zones, there is a guest house limitation which applies to tiny homes as well.

Each year, county officials award 12 property owners in rural zones a permit to build a guest house, which is not attached to their main house. That means, no more than one tiny home can be on the property with another house in the country unless a permit through this lottery is obtained.

“[County code] really restricts anyone living together, like forming a community or sharing land to save money,” said Wild.

On June 6, San Juan County Building Advisory members recommended that this ban would be lifted in rural zones for tiny homes, sized 400 square-feet or lower. They also requested units’ utilities to be “self-contained.” This would allow alternative sources like composting toilets and rain catchment systems, which is currently prohibited for detached guest houses.

That 2007 limitation was a “compromise,” according to BAC secretary Richard Russell to litigation brought after the county allowed every parcel in a rural zone to include a detached guest house.

State officials ruled that the possibility of doubling the density in the rural zones did not match the density projection laid out in the county comprehensive plan. The comprehensive plan sets the county’s goals for growth and is overseen by the state.

The new allowance for the additional property will be different, attests Russell. BAC members will create a study to address the visual and environmental impact of allowing tiny homes in the area. A study wasn’t performed last time, he said, which opened the doors for appeals.

“There are people living in this county who would like to continue living here but can’t afford to,” said Russell. “Do you decide there’s no place for them and have them move away?”

The comprehensive plan will be updated this year and density limits could be increased, according to San Juan County Councilman Jamie Stephens. Yet, even if the guest house limit is lifted, what assurance is there that these dwellings — whether a tiny house or guest house — will be long-term rentals at affordable costs?

“I haven’t had that questioned answered,” said Stephens. “If [a tiny house] is a guest house, that doesn’t solve affordable housing.”

To Stephens, adding more dwellings to rural zones doesn’t, in itself, create affordable housing, as the property owners set the rental prices and lengths.

What makes the islands unique, said Stephens, is the county’s owner/builder permits, which allows property owners to build their own structures under 2,000 square feet, with their own materials. They’re also about half the cost of the standard building permit and don’t have to meet standard building code, just a life safety inspection. This helps islanders build tiny homes as the main structure on their properties at reasonable prices.

Windermere broker Sarah Jones, who lives in a roughly 700-square-foot home herself, said the owner/builder permit proves the county is not the obstacle in using tiny homes.

“The county is actually very supportive of building tiny structures,” she said.

The bigger issue, said Jones, is many county developments’ rules, which sometimes set size limitations and exclude homes on wheels. These prohibit living in tiny homes on trailers, as well as mobile homes and recreational vehicles. The county, itself, has no limits on the size of new structures or living in trailers.

The Town of Friday Harbor code does prohibit living in RVs and tiny homes on wheels in residential areas. This maintains community characteristics, said Mike Bertrand, with the town’s planning department.

“If we opened that up [in residential zoning], in the summertime, in every driveway, there’d be a camper and someone living in it,” he said. “That’s not what a neighborhood should be.”

Dense areas — like Friday Harbor on San Juan, Eastsound on Orcas and Lopez Village on Lopez — are where multiple tiny homes could be installed today. Bertrand said there are about 12 tiny homes on foundations in the town.

Yet, hooking up to shared water and sewer systems in multi-unit zones can be pricey.

In a multi-family zone in town, said Bertrand, it costs $10,800 to hook up to water, which can be split among units. Each unit would also pay $9,100 to hook up to the sewer.

In a Lopez Village multi-unit zone, connecting to water through the Fisherman Bay Water Association would cost about $8,000, then about $1,500 for the materials and labor to add the property to the system.

In Eastsound, it would cost $12,700 to connect to Eastsound Water. Paul Kamin, general manager of the association, said a tiny house might not be able to qualify for a ‘smaller membership’ than the normal single family home. Inside Eastsound Water’s service area on Orcas, he said, guest houses can use a half connection, since metering records have shown those residents use half the water as the main house. County officials could make some changes to lower costs, but the system is mostly regulated by the state, he added.

No recommendations have been approved by council yet. Meanwhile, Wild is still trying to help islanders find homes.

“Almost every business I talked to said they can’t hire staff because they can’t find housing,” he said. “We’re trying to address that.”