Ocean acidification is a threat to marine ecosystems around the world and the Salish Sea is among those most vulnerable to its effects. Recognition of the problem is new and there are practically no measures in place to regulate or manage it.

Enter Dr. Nina Bednaršek, a scientist with the Southern California Coastal Waters Research Project and winner of this year’s Salish Sea Science Prize. Through years of groundbreaking science, Bednaršek and her collaborators discovered that tiny marine mollusks called pteropods can be used to understand the biological effects of ocean acidification, which is a growing threat thanks to human-caused pollution. Pteropods are an indicator species for the ecosystem as a whole.

“The Salish Sea is one big ocean acidification hotspot,” said Bednaršek. “It’s corrosive from late fall through winter, including early spring. It’s so severe that it’s not just impacting pteropod shells; it’s impacting their survival.”

The SeaDoc Society, a program of the UC Davis Karen C. Drayer Wildlife Health Center, awards the Salish Sea Science Prize every two years to recognize scientists whose work will result in the improved health of fish and wildlife populations in the Salish Sea. It comes with a $2,000, no-strings-attached cash prize and will be awarded to Bednaršek on April 4, at the opening plenary session of the Salish Sea Ecosystem Conference in Seattle.

There are currently no established ways to evaluate and regulate the effects of ocean acidification, but Bednaršek’s study of pteropods has laid the foundation for that to change.

Her work began in the Scotia Sea off the Southern Ocean, which is an intense upwelling region where deep sea water naturally rises to the surface – a characteristic shared by the west coast of North America, including the Salish Sea where she would go on to study extensively.

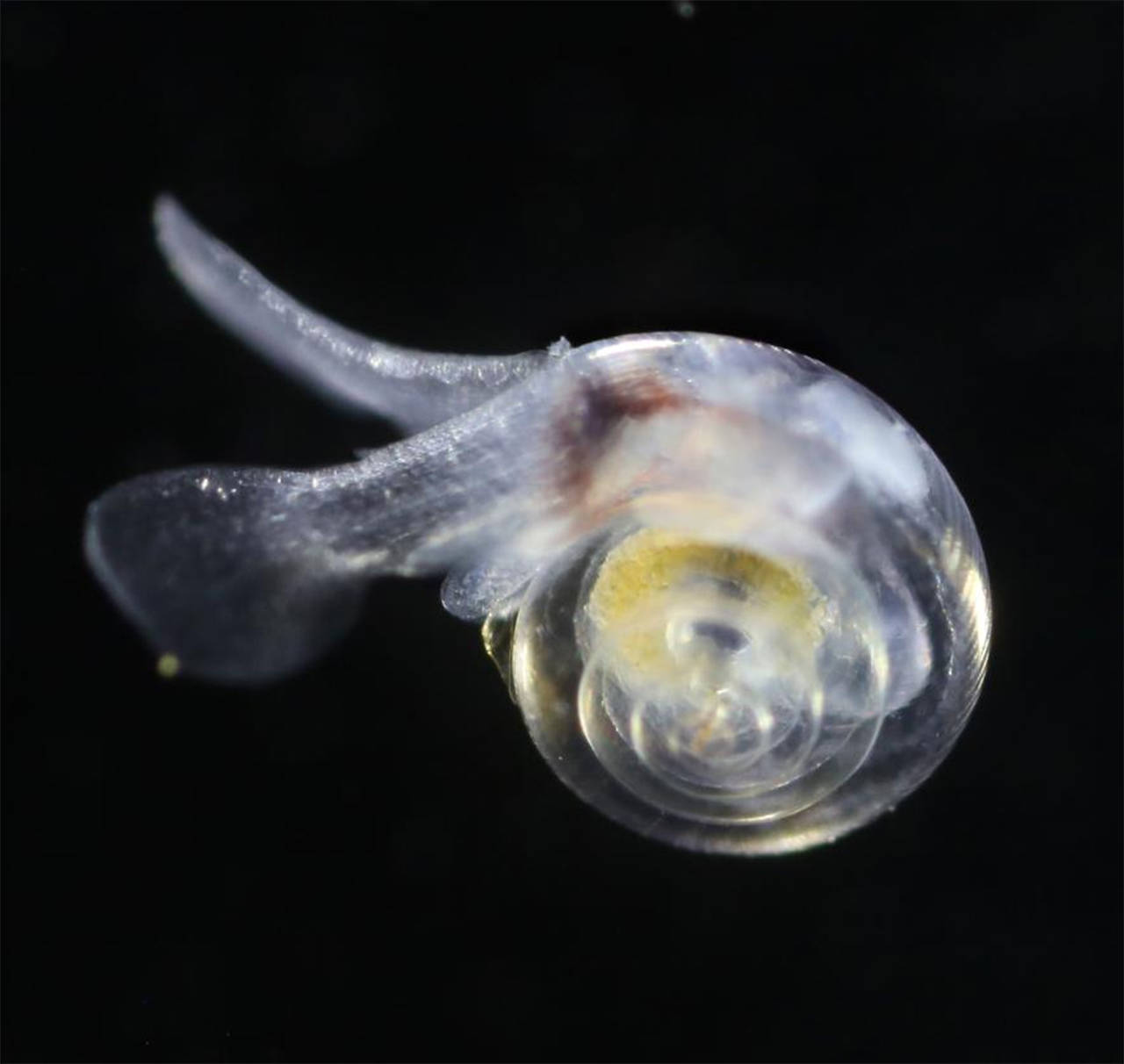

Throughout her studies in these ocean acidification hotspots, Bednaršek and her collaborators observed the severe dissolution of pteropod shells, which are typically about as thin a human hair.

“Under normal conditions the shell is smooth,” said Bednaršek. “But in corrosive waters, it becomes opaque and fragmented.”

As their shells become damaged, their stress levels rise and they reallocate energy in an attempt to fend off death, leaving them heavily compromised and prone to infection and predation. Pteropods are a crucial food source for many fish in the Salish Sea, including salmon.

Within a few years, Bednaršek published nine papers describing how pteropod dissolution correlates with physical and chemical stressors in our region, which can be tied to sewage dumping, storm drain runoff, carbon emissions and climate change. The highest impacts she has observed throughout her studies have been in the Salish Sea.

Bednaršek’s work shows that more than half of the pteropods along the west coast already show evidence for severe shell dissolution, and the individuals affected could be correlated with the local ocean acidification stress.

Bednaršek and her collaborators have already developed a set of ocean acidification indices that could be used by coastal States and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to address water quality issues with respect to ocean acidification, and she has translated that research so that it can be used in water quality management.

“Science is crucial in driving changes in policy and management,” said Bednaršek. “You need solid scientific evidence to detect how humans are impacting the environment.”

Dr. Bednaršek’s work makes it clear that ocean acidification is already having an effect on biological organisms and is an unprecedented threat on our ocean’s ecosystems. Her work with this tiny creature is filling large gaps needed to drive the kinds of management actions that will be needed to mitigate ocean acidification.

“Science plays a critical role in restoring ecosystems like the Salish Sea,” said SeaDoc Society Science Director Joe Gaydos. “The Salish Sea Science Prize is designed to recognize how science helps us figure out what to do when we are faced with evolving challenges like ocean acidification. We couldn’t be more honored to give Dr. Bednaršek this award.”