Roy Matsumoto bested the Great Depression and discrimination of his day only to find himself branded an “enemy alien” by the country of his birth, and then banished to an internment camp alongside so many other Americans of Japanese ancestry after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

He experienced so much before the age 29. At that age time was on his side and Matsumoto would make the most of it.

The one thing he could not overcome, however, was time itself.

Matsumoto died Monday, April 21, at his San Juan Island home. He was 100.

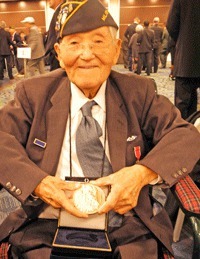

The day before, the Matsumoto family celebrated Easter Sunday with a dinner of fried chicken, a selection dear to Matsumoto’s heart in that it personified the triumph over Japanese troops in the jungles of Burma and the daring role he played in helping to orchestrate that defeat, as well as the acts of bravery for which he would later earn a wealth of military awards and decorations, in addition to the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest civilian award.

“Easter was a really good day for him,” Matsumoto’s daughter Karen said. “He was feeling really upbeat and vibrant. It’s really a shock for all of us.”

Born in Long Beach, Calif., in 1913, Matsumoto spent his early childhood in Southern California until, at the age of eight, he returned along with his family to their ancestral home of Japan.

Nine years later, in 1930, Roy would cross the Pacific Ocean once again, headed back to Long Beach to attend high school and, in what would prove a most fateful episode, he would take a job in a relative’s grocery store and become familiar with the many dialects spoken by customers of Japanese descent along his delivery route.

Karen Matsumoto said that her father’s health had declined rapidly in the past several weeks. Up until about two weeks ago, she said he had been riding along in the family car and helping collect donated eyeglasses on behalf of the San Juan Island Lions Club, a program he championed and had been involved in for years.

Still, she said that her father passed away on his own terms.

“He always said that he wanted to die here at home, watching the hummingbirds out the window,” she said. “Considering all the wear and tear over years, he got a lot of mileage out of that body.”

Matsumoto is survived by his wife, Kimiko, daughters Fumi and Karen, sons-in-law Richard and John, and three grandchildren.

Already a decorated war hero when he and his wife, Kimiko, moved to San Juan Island in the late 1990s, Matsumoto retired from the Army as a master sergeant in 1963. He was inducted into the U.S. Army “Ranger Hall of Fame” in 1993 and four years later into the “Military Intelligence Hall of Fame” as well.

Credited with having saved his company from being overrun by a battalion of advancing Japanese troops during the siege of Burma, Matsumoto proved every ounce the definition of military hero during service to his country as part of the fabled Merrill’s Marauders in WWII, putting his language skills and life at risk to safeguard those of his comrades.

More recently, Matsumoto became the face of and central figure in an award-winning documentary that chronicles the riveting, complex story of a Japanese immigrant family torn apart by WWII.

Produced by Bainbridge Island-based Stourwater Pictures, “Honor & Sacrifice: The Roy Matsumoto Story” has been featured in no fewer than seven film festivals since its release two years ago and was selected “Best Short Documentary” at the 2013 Gig Harbor and 2013 Port Townsend film festivals, respectively.

In early April, the Organization of American Historians bestowed one of its highest honors on “Honor and Sacrifice,” the 2014 Erik Barnouw Award, in recognition of the film’s contribution to American history.

Matsumoto was never shy about sharing his life’s story.

“He was a total character,” Karen Matsumoto said of her father, “one of a kind.”