Norm Stamper says United States law enforcement is a “paramilitary bureaucracy” that can only be fixed with radical law and policy changes.

“There are pockets of goodness and tradition worth preserving but our principles and priorities are really screwed up,” he said. “You can’t arrest yourself out of social problems.”

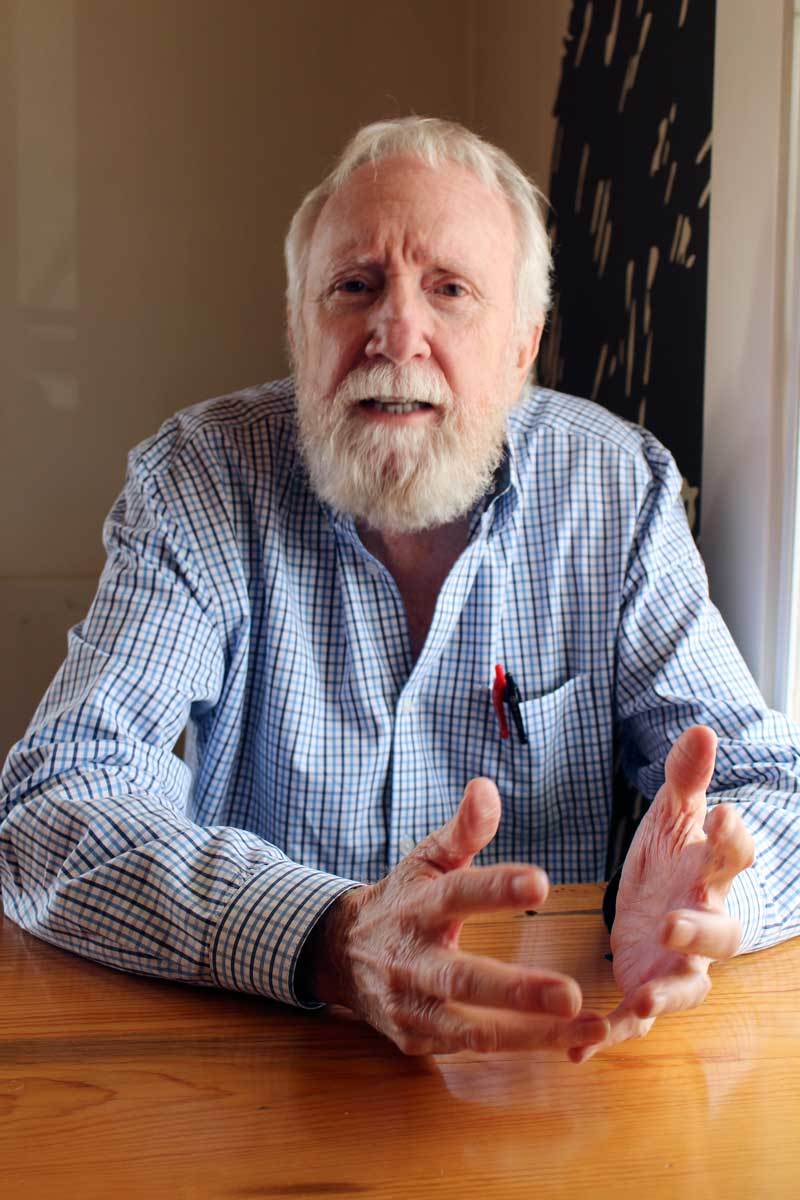

As a police officer, scholar and author, former Seattle Police Chief Stamper has spent his life dedicated to improving policing. His new book “To Protect and Serve: How to Fix America’s Police” offers a different model for departments: community-based policing. He calls for changes in the federal government’s role as well as citizen participation in policymaking, program development, entry-level and ongoing training, oversight of conduct, and joint community-police crisis management.

Stamper will be reading and signing copies of the book from 1:30 to 3:30 p.m. in the Madrona Room at Orcas Center on Sunday, June 26.

“The police in America belong to the people – not the other way around. But that’s not what police officers are taught,” he said. “It puts us farther away from the definition of true community policing.”

Stamper said three factors contributed to militarization of law enforcement: citizens using guns on police officers, the war on drugs and the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks. He believes police officers have become alienated from those they’ve been hired to serve.

The early years

Stamper became a police officer by chance. He was married and working as a veterinary assistant at 20 years old when a friend asked him to tag along while he took the San Diego police academy entrance test. Stamper says the promise of a corned beef sandwich and beer motivated him to say yes. While waiting at the testing center, he was invited to take the exam as well. Stamper passed, enrolled in the academy and began a career that would forever change his life.

From the moment he put on the uniform, Stamper wanted to be a different kind of cop – one who didn’t use racial slurs, anger and abuse to maintain power over others.

But during his first year on the force, everything he had aspired to be went straight out the window. He said the job was about “meeting quotas that translated into revenue.”

“Despite the best of intentions, I was saying and doing things I had never done in my life,” he said. “I was abusing the very people I had sworn to serve. The power went straight to my head.”

The defining moment of his career came when a prosecutor called him to task for an unjustified arrest.

“He said to me, ‘Does the constitution of the United States mean anything to you?’ I had a visceral reaction to that. And I made a decision to become a change agent.”

Realizing that systemic changes were in order, he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in criminal justice and a PhD in leadership and human behavior, all while rising up the ranks in the San Diego Police Department.

In the 1970s, he started a major overhaul of the department that included cutting ranks, decreasing bureaucracy, increasing communication and introducing community policing. The reaction from his officers was less than enthusiastic.

“They said, ‘You are asking us to be social workers.’ But the police are the first responders in everything from domestic violence to bank robbery. Cops are called into people’s lives in the most vulnerable and tragic moments,” Stamper said.

When he was recruited in 1994 to serve as the Seattle police chief, a position he held until 2000, he brought those same principles to fruition and created a youth and family protection bureau. He was later criticized for his department’s use of tear gas, pepper spray and stun grenades during the World Trade Organization protests in Seattle in 1999. It was an experience that he says taught him which tactics make sense, and which do not.

After his retirement in 2000, Stamper became a public speaker, wrote columns for the New York Times, the New Yorker and the Seattle P-I, appeared on national television shows and published the book “Breaking Rank: A Top Cop’s Expose of The Dark Side of American Policing.”

Stamper says his idea of community policing is more radical today. He hopes to see a partnership between citizens and those sworn to protect them.

“Americans have become conditioned to a bystander mentality. And some of those Americans are wearing uniforms,” he said.