by Russel Barsh

and Madrona Murphy

Special to the Sounder

More than 150 years ago, before the American Civil War, and even before the so-called Pig War, the San Juan Islands were already a subject of serious study by American and British scientists. They accompanied American railroad surveyors who crossed the continent in the early 1850s searching for practical routes to the Pacific Ocean, and some of them remained in California and the Oregon Territory, collecting more specimens.

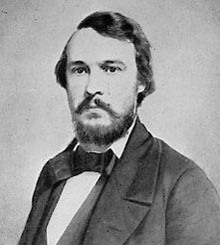

When the British Empire disputed U.S. claims to the San Juan Islands in 1855, both governments appointed boundary commissions to survey what they believed to be the correct dividing line. The British team arrived at Victoria in 1857 accompanied by David Lyall, a widely traveled botanist, as well as a zoologist and a geologist. The U.S. team recruited three researchers who happened to be on the West Coast already: George Suckley, an Army surgeon and amateur zoologist stationed at Steilacoom; George Gibbs, Harvard educated lawyer and student of Native American languages in Puget Sound; and C.B.R. Kennerly, a young Virginian fresh out of Dickinson College where he had studied ornithology with Spencer Baird, director of the National Museum (now the Smithsonian).

Baird had arranged for Kennerly to accompany the railroad surveyors to the Pacific Coast, and recommended him to the boundary commission. Kennerly was just 28 years old when he accepted this new assignment. He was supplied with copper cans, laboratory alcohol, a primitive camera and instructions to collect animals and plants throughout the sound and send them back to Washington, D.C., by any ships available. He was also told to evaluate the natural resources and potential economic value of the San Juan Islands.

The Americans built a camp of tents and shacks at Semiahmoo Bay near present-day Blaine where Kennerly was to live for the next three years, venturing to the islands whenever he could secure a suitable boat. His first visit, in December 1857, began with a gale that forced his crew ashore for a week near present-day Eastsound.

A more systematic exploration of the islands was undertaken over a period of six weeks in 1860. At the time there were fewer than 50 settlers on San Juan Island, perhaps a dozen on Orcas and none on Lopez. One “horrible” road penetrated the central valley of San Juan Island, and when trying to explore the north end of the island, Kennerly’s party was stymied by the almost impenetrable swamps which they encountered. “It was by far the worst traveling that we have yet had,” he wrote. “It was absolutely awful. We got lost repeatedly and but for our compass might have had trouble in returning.”

Kennerly’s notes provide a window to island ecology before it was transformed by a century of Euro-American farming, logging, sheep and roads. He saw elk on Orcas, wolves on Lopez and San Juan. He visited an “oak prairie” on central San Juan Island where relic trees can be seen today, but did not mention oak stands anywhere else in the islands. Kennerly realized that the most fertile land was “prairie” or low-lying seasonal wetlands covered by bracken ferns where they had been “cleared by fire.” He observed extensive burnt-over areas on west Orcas, Blakeley, Decatur, Lopez, south San Juan and Shaw. He described the woodlands as “thrifty,” by which he meant young, tall thin trees, consistent with extensive fire clearing by native peoples.

Kennerly made unusual observations for a naturalist of his era and relative youth.

“All of these islands appear to be gradually rising as shown by the marks on the bluffs and the character of the alluvial soils,” he noted in his journal.

He also recognized that island streams were mostly seasonal, and that species diversity in the islands was relatively low. He made major errors, too, such as his report that “good grass abounds everywhere in the hills” of the islands based on mid-winter observations at a distance. He saw little grass on the hills he actually scaled, and on Stuart Island he observed: “On these grassy summits and slopes, grow in quantities a kind of Kamas, which the Indians gather for food.”

Camas does not compete well in grass, we have found. What Kennerly probably saw on hilltops in winter were early shoots of camas, brodiaeas and onions, which can form a dense turf.

Kennerly and Gibbs employed Coast Salish people as collectors of specimens and turned to Native languages for insights into the classification and ecology of local species including fish, birds and mammals. Kennerly even traveled to Point Roberts to participate in the Native reef-net fishery and collect specimens. His use of local knowledge, novel in the 1850s, only became widely recognized as a tool of field biology in the 1980s.

Tragically, Kennerly did not live to publish his findings; he died on shipboard on his way home around Cape Horn on the eve of the Civil War in 1861. His field notes and specimens went into cabinets and drawers throughout the Smithsonian where hundreds of specimens can still be found, although many were lost, including pressed plants and glass plate photographs. His meticulous analysis of salmon species, based on native languages, was disregarded when Suckley published the first monograph on Pacific salmon and trout in 1874, but was largely vindicated by genetics in the 1990s.

Russel Barsh and Madrona Murphy are following in C.B.R. Kennerly’s footsteps by continuing to document the biodiversity and biogeography of the San Juan Islands as researchers for the Lopez-based nonprofit Kwiaht. Russel has been annotating Kennerly’s papers and studying his collections since 2002, producing articles and conference papers on Kennerly’s salmon science and Native dogs. His biography of Kennerly will appear on History Link as part of the San Juan County Writing Our History Project.