Big tsunamis come every 300 to 600 years, and the last one for the west coast was 315 years ago, which means a disaster could be headed our way.

“There are a number of quake scenarios that could impact the islands,” said Brendan Cowan, director of the county’s Department of Emergency Management. “All are real, and could potentially happen tomorrow.”

The good news is that when the tsunami comes islanders can be ready.

According to the DEM’s new webpage entitled Common Tsunami Questions, “In the most likely scenario, San Juan County will have plenty of warning (due to the large quake we feel) before a tsunami in the form of an extremely large earthquake.”

The tsunami could come in 45 minutes or less after a large quake, which is defined as rating 5.0 or greater on the logarithmic scale. Although 9.0 would be incomprehensibly larger than a 5.0, Cowan describes both as large enough to cause concern.

“In general, the larger the quake, the bigger the tsunami, but there’s an almost limitless number of scenarios that could cause a tsunami,” he said. “By focusing on the 9.0 quake with our maps, we’re looking at the most studied/best understood and one of the potentially most damaging events.”

What complicates matters is that not all quakes cause tsunamis. The quake has to lift the sea floor to be followed by a tsunami, and according to Cowan, the majority of undersea quakes don’t cause a tsunami.

To understand how likely it is that a tsunami is headed our way one has to look back to 1700 – and a forest submerged by salt water. For many years quake experts believed that the closest fault, the Cascadia subduction zone, was safely aseismic. When they found mysteriously sunken Northwest forests that appeared to have been killed by salt intrusion in the year 1700, their conclusion changed.

It turns out that the eastward-moving Juan de Fuca tectonic plate is not sliding smoothly beneath the westward-moving North American plate; instead, it’s bunching up, building up tremendous pressure that scientists believe will eventually let loose in the space of a few minutes.

If the fault’s five segments all “go off” at once, a 9.0-plus magnitude megaquake could launch twin killer tsunamis, one toward the Pacific Coast and one toward Japan.

Seismologists now believe that’s what caused what is known as the Orphan Tsunami, which killed 1,000 people in 1700. When the plates finally slipped free, the pent-up Pacific Coast dropped by about five feet, submerging the forest.

Predictions as to when the plates will roar again vary, but the Washington State Department of Natural Resource Chief Hazards Geologist Tim Walsh has said six past earthquakes affecting Washington have occurred 500 to 550 years apart. The year 2015 will make it 315 years and counting since the last big event. Canadian and U.S. experts have offered probabilities of 14 to 29 percent that the event could occur during the next 50 years.

Where to run?

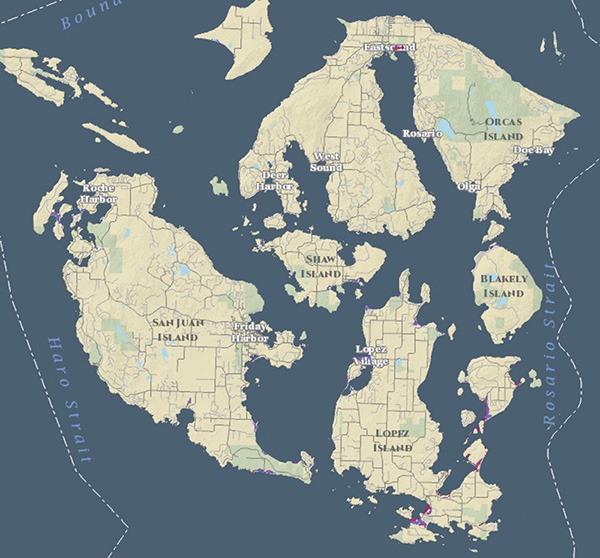

The DEM just released an online map tool that allows islanders to view the tsunami risk following a Cascadia quake. You can see the maps at http://sjcgis.org/tsunami-inundation/. According to Cowan, this is the first time that the department has had a data-driven picture of how the tsunami will affect San Juan County. This data has been collected over the span of 10 years. Prior to that, predictions of the tsunami effects were based on speculation or interpretation from work done on either a larger scale or for locations other than the San Juans.

Since the tsunami hit Japan in March 2011, Cowan said there has been a lot of confusion in the community about tsunami risks.

“The very idea of them can understandably bring up strong emotions, likely due to the extremely vivid images we’ve seen from Japan and the Indian Ocean,” he said.

Some of the most common misunderstandings Cowan hears from the public is that what happened in Japan would be replicated here, and that if you know it’s coming you should get in a boat and ride it out.

Apparently jumping in your boat has worked in outer coast areas where deep open water is close at hand, but will not work here because of the complexity of island waters, which create an unpredictable environment and current speeds approaching 15 knots or more.

Another myth is that a tsunami would only impact the west side of San Juan or Lopez. According to recent data, Crescent Beach and Lopez would be most impacted by a tsunami with flow depths up to 18 feet.

Cowan wants people to understand that the tsunami is not so much a wave but more like an extremely fast-moving and amplified tidal cycle.

“We want this to be a tool that educates islanders about the risk and teaches them that in the event of a big quake, people near the water should calmly collect their family and things and head for high ground, say 35 feet or more above the water,” Cowan said. “In the islands, high ground is never too far away.”

The vast majority of the islands will not be inundated by tsunami water. According to Cowan, islanders should be aware that the first surge is often not the biggest. Tsunami impacts can continue for 12 hours or more after the first effects.

How to stay alive

Cowan hopes the launch of the online maps will offer reassurance to those who fear the tsunami will be catastrophic. At the same time he wants to raise awareness that tsunamis are worth paying some attention to.

“The whole idea is to strike a balance between needlessly sowing fear, but also not putting our heads in the sand,” he said. “The worse thing for me would be if when it happens there’s someone killed or injured who had no idea at all that a tsunami was a possibility.”

The hazard from tsunamis is not so much in the wave, but what it carries in its wake.

According to the DEM’s website, “the danger comes from rapidly rising water, as well as fast-moving debris entrapped in the flow, which includes boats, docks, driftwood logs and other items become potentially devastating battering rams.”

Avoiding these objects is the first step to surviving the disaster. On the islands it is likely that people will be cut off from the mainland for weeks, meaning there will be a shortage of food, fuel and medical care. Water and septic systems could be compromised. Ferry service, electricity and Internet might be lost for a long period of time. Cowan recommends that islanders should be prepared to be completely self-sufficient for seven to 10 days.

For detailed information on how to be self-reliant after a tsunami, visit sanjuandem.net.

“Steps to prepare don’t need to be especially expensive or time consuming, and there’s no good reason not to start preparing,” said Cowan. “My office is always willing to help any person, family, business or organization who needs some help getting going.”

You can contact Cowan by email at dem@sanjuandem.net or by phone at 370-7612.