Contributed by Kwiaht director Russel Barsh.

A conspicuous reddish brown bloom appeared in East Sound in the final days of August, triggering several calls to the Indian Island Marine Health Observatory’s ITOX hotline (468-ITOX).

Samples were collected and analyzed by local volunteers on Orcas, by University of Washington phycologist Dr. Robin Kodner, who is advising the ITOX program, and her colleague Dr. Charlie O’Kelley. Volunteers were trained by Dr. Vera Trainer and Brian Bill of NOAA’s SoundToxins program.

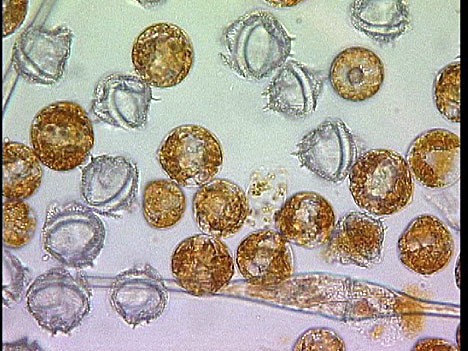

The bloom was not one, but several different organisms that appear to have been changing from day to day. One of them is particularly interesting to scientists: the round armor-plated dinoflagellate Gonyaulax, which produced the reddish color. Gonyaulax is interesting because it behaves differently under different local conditions, for reasons that remain unclear. Some Gonyaulax species sometimes produces saxitoxin, a powerful neurotoxin most commonly associated with other dinoflagellates in Puget Sound. Saxitoxin is a cause of paralytic shellfish poisoning. At other times, one known species of Gonyaulax produces yessotoxin, a different chemical compound that affects heart and kidney function as well as the nervous system. Sometimes Gonyaulax produces no toxic substances. Scientists like Robin Kodner and Brian Bill are eager to find out what conditions trigger a toxic episode.

Dr. Kodner notes that even when a bloom is non-toxic, the decay of such a large mass of organisms can exhaust the oxygen dissolved in seawater, resulting in anoxia or “dead zones.” Kwiaht director Russel Barsh adds that certain kinds of dense blooms, like ones seen in late June this year, may also pack the gills of fish and cause respiratory distress, “like trying to breath in a sandstorm.” He is working with Dr. Kodner and her students on testing juvenile salmon with respiratory distress for exposure to the raphidophyte Heterosigma akashiwo, which bloomed county wide in late June.

“Our focus is what triggers the blooms, and their impact on marine ecosystems,” Barsh said.

It is unusual for scientists to be able to sample a bloom like this at several places over several days as it grows and changes.

“Things change fast in blooms,” Dr. Kodner explains. “I’m most curious about what was stimulating the bloom at such a late date in the summer.” She adds that callers to ITOX help scientists find and track local blooms, and find out what makes them form and change. Blooms are a natural phenomenon and are not a cause for concern unless they become persistent or toxin is actually produced. Since farmed shellfish are routinely tested by the State Department of Health, they are a safe bet even when local beaches are closed.